Havorn's Story -

the beginning

Lee H. Ehrheart

In 1965, my wife, Greta, and I, with our two-year-old son, Jens, went to Greta's native Norway to buy a traditional Norwegian double-ended fishing boat. We planned to convert this vessel for deep-sea world cruising. We found the Havorn, a Colin Archer designed fishing boat, recognized her potential to fulfil our desires, and bought her. We then sailed to Tomra in Romsdalen to the boatyard of Elias Tomren, master boatbuilder and shipwright, to convert Havorn to our needs as a cruising sailboat.

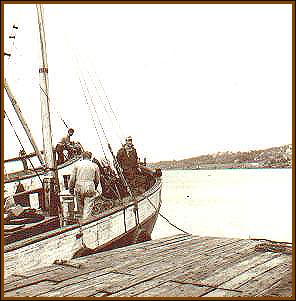

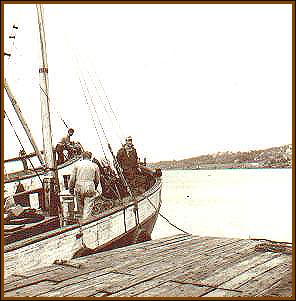

At Tomra we joined up with some friends from California, Jeff and Jessica Lane (and their young son Jonathan) who were doing a similar thing with another Norse fishing boat called Gladhval. At Tomra we joined up with some friends from California, Jeff and Jessica Lane (and their young son Jonathan) who were doing a similar thing with another Norse fishing boat called Gladhval.  The photo here shows the two boats preparing to go up the slipway for the long job of conversion. Havorn is closest to the camera, with Kristofer Gjerde, the yard foreman, on the foredeck. In the background, Jeff Lane is casting off the docklines in preparation for moving out to allow Havorn up on the slipway first. The man on Havorn's deck with his back to the camera is Elias Tomren. We were all full of excitement as we moved into this phase of bringing our dreams of cruising the world in seaworthy and comfortable boats closer to reality. The photo here shows the two boats preparing to go up the slipway for the long job of conversion. Havorn is closest to the camera, with Kristofer Gjerde, the yard foreman, on the foredeck. In the background, Jeff Lane is casting off the docklines in preparation for moving out to allow Havorn up on the slipway first. The man on Havorn's deck with his back to the camera is Elias Tomren. We were all full of excitement as we moved into this phase of bringing our dreams of cruising the world in seaworthy and comfortable boats closer to reality.

Our intention was to haul both boats out on the same slipway, leaving the boatyard's other slipways free for business as usual. Our intention was to haul both boats out on the same slipway, leaving the boatyard's other slipways free for business as usual. It required careful alignment of both boats over the slipway to make certain that Havorn was as far forward as possible, leaving room for Gladhval behind. It required careful alignment of both boats over the slipway to make certain that Havorn was as far forward as possible, leaving room for Gladhval behind.

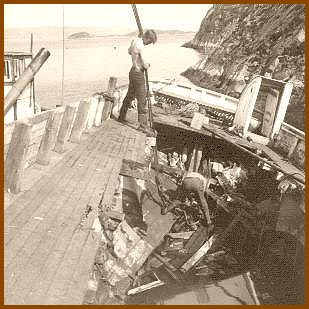

We planned to do much of the work of rebuilding and converting the boats ourselves, with occasional help from the yard when we needed it. In the photo to the right you can see me on the foredeck, leaning over and looking anxious as well as fascinated by the Norwegian way of hauling boats out - an improvement over the methods used by the ancient Vikings, but still different from the American boatyards I knew. Here, the boat is being positioned over a long plank which slides in the groove of the slipway. Once in position, the plank is pulled forward by a power winch, hauling the boat out of the water. As she rises from the water, she comes to rest on a rail on one side, which is greased and provided with sliding blocks for the hull to rest against. Once ashore, the hull will be propped up with supports which allow her to sit full upright. We planned to do much of the work of rebuilding and converting the boats ourselves, with occasional help from the yard when we needed it. In the photo to the right you can see me on the foredeck, leaning over and looking anxious as well as fascinated by the Norwegian way of hauling boats out - an improvement over the methods used by the ancient Vikings, but still different from the American boatyards I knew. Here, the boat is being positioned over a long plank which slides in the groove of the slipway. Once in position, the plank is pulled forward by a power winch, hauling the boat out of the water. As she rises from the water, she comes to rest on a rail on one side, which is greased and provided with sliding blocks for the hull to rest against. Once ashore, the hull will be propped up with supports which allow her to sit full upright.

Here you see the Viking method, using rollers and manpower - lots of manpower - to haul out a ship. We all definitely preferred the modern methods, even at the loss of a little romance. There was romance enough in what we were doing anyway - and plenty of hard work as well. Here you see the Viking method, using rollers and manpower - lots of manpower - to haul out a ship. We all definitely preferred the modern methods, even at the loss of a little romance. There was romance enough in what we were doing anyway - and plenty of hard work as well.

The idea of having both boats up on the same slipway and being able to help each other from time to time worked out well. Here I am standing on Havorn's rail cap, handing a long bilge stringer (a longitudinal interior support for the frames) in to Jeff, who is inside Gladhval. This was definitely a two-man job, as were many others. The idea of having both boats up on the same slipway and being able to help each other from time to time worked out well. Here I am standing on Havorn's rail cap, handing a long bilge stringer (a longitudinal interior support for the frames) in to Jeff, who is inside Gladhval. This was definitely a two-man job, as were many others.

Although Jeff, Jessica, and I had all had done repairs and rebuilding yachts and small boats, this was our first experience with the thick planks, heavy sawn frames, and other massive timbers of these classic Norwegian deep-sea vessels. Although Jeff, Jessica, and I had all had done repairs and rebuilding yachts and small boats, this was our first experience with the thick planks, heavy sawn frames, and other massive timbers of these classic Norwegian deep-sea vessels.

Havorn's planks are 2" furu (long-leaf yellow pine), a close-grained, strong Norwegian pine traditionally used for shipbuilding. Her frames are sawn furu, 8" x 6" doubled on 18" centers. The frames are set in pairs, sistering each other for added strength. They are fastened together with trenails (pronounced "trunnels"), long 1=1/4" furu rods, wedged on both inside and outside for a solid fit. Although these traditional fastenings are a lot more trouble to make and install than modern bolts, they are well worth it. Once in and the boat back in the water, the planks and fastenings both swell a bit and hold very securely. And of course the fastenings never rust or corrode, damaging the planks. Havorn's frames are as strong as the day they were made. The Lanes and I made our own trenails, using a lethal little machine which had a tendency to catch in the grain and fling the trenail across the workshop. We tried to make them when there was no one else around to get hit by unexpected flying chunks of furu. Havorn's planks are 2" furu (long-leaf yellow pine), a close-grained, strong Norwegian pine traditionally used for shipbuilding. Her frames are sawn furu, 8" x 6" doubled on 18" centers. The frames are set in pairs, sistering each other for added strength. They are fastened together with trenails (pronounced "trunnels"), long 1=1/4" furu rods, wedged on both inside and outside for a solid fit. Although these traditional fastenings are a lot more trouble to make and install than modern bolts, they are well worth it. Once in and the boat back in the water, the planks and fastenings both swell a bit and hold very securely. And of course the fastenings never rust or corrode, damaging the planks. Havorn's frames are as strong as the day they were made. The Lanes and I made our own trenails, using a lethal little machine which had a tendency to catch in the grain and fling the trenail across the workshop. We tried to make them when there was no one else around to get hit by unexpected flying chunks of furu.

Winter in the boatyard. Norwegian winters are long and they are cold. We kept warm by working hard.

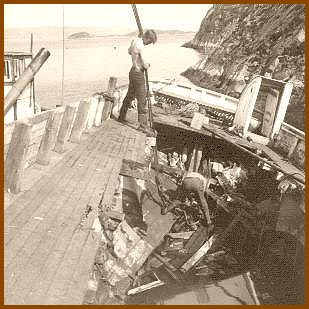

Spring eventually came, the boats were launched, and we set off on our travels. One of our first stops was this derelict, long-abandoned vessel to salvage some of the ballast. Havorn still has some of that ballast aboard. Spring eventually came, the boats were launched, and we set off on our travels. One of our first stops was this derelict, long-abandoned vessel to salvage some of the ballast. Havorn still has some of that ballast aboard.

Since then Havorn has voyaged to the South Pacific, where she cruised for many years. About 25 years ago, I brought her to the Pacific Northwest, where she has cruised since. Her current home port is Seattle. I'll get more of Havorn's story (at least in brief) and photos up on these pages when I have time. Since then Havorn has voyaged to the South Pacific, where she cruised for many years. About 25 years ago, I brought her to the Pacific Northwest, where she has cruised since. Her current home port is Seattle. I'll get more of Havorn's story (at least in brief) and photos up on these pages when I have time.

Back to the Havorn page.

Back to the Photos of Havorn page.

Havorn Marine Services, Inc.

|

Here you see the Viking method, using rollers and manpower - lots of manpower - to haul out a ship. We all definitely preferred the modern methods, even at the loss of a little romance. There was romance enough in what we were doing anyway - and plenty of hard work as well.

Here you see the Viking method, using rollers and manpower - lots of manpower - to haul out a ship. We all definitely preferred the modern methods, even at the loss of a little romance. There was romance enough in what we were doing anyway - and plenty of hard work as well.

Since then Havorn has voyaged to the South Pacific, where she cruised for many years. About 25 years ago, I brought her to the Pacific Northwest, where she has cruised since. Her current home port is Seattle. I'll get more of Havorn's story (at least in brief) and photos up on these pages when I have time.

Since then Havorn has voyaged to the South Pacific, where she cruised for many years. About 25 years ago, I brought her to the Pacific Northwest, where she has cruised since. Her current home port is Seattle. I'll get more of Havorn's story (at least in brief) and photos up on these pages when I have time.

The photo here shows the two boats preparing to go up the slipway for the long job of conversion. Havorn is closest to the camera, with Kristofer Gjerde, the yard foreman, on the foredeck. In the background, Jeff Lane is casting off the docklines in preparation for moving out to allow Havorn up on the slipway first. The man on Havorn's deck with his back to the camera is Elias Tomren. We were all full of excitement as we moved into this phase of bringing our dreams of cruising the world in seaworthy and comfortable boats closer to reality.

The photo here shows the two boats preparing to go up the slipway for the long job of conversion. Havorn is closest to the camera, with Kristofer Gjerde, the yard foreman, on the foredeck. In the background, Jeff Lane is casting off the docklines in preparation for moving out to allow Havorn up on the slipway first. The man on Havorn's deck with his back to the camera is Elias Tomren. We were all full of excitement as we moved into this phase of bringing our dreams of cruising the world in seaworthy and comfortable boats closer to reality. It required careful alignment of both boats over the slipway to make certain that Havorn was as far forward as possible, leaving room for Gladhval behind.

It required careful alignment of both boats over the slipway to make certain that Havorn was as far forward as possible, leaving room for Gladhval behind.